Note: This article was updated on March 18, 2020 at 12 p.m. to reflect new guidance from the Office for Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Education. It was previously updated on March 13 to reflect guidance from the Department of Education.

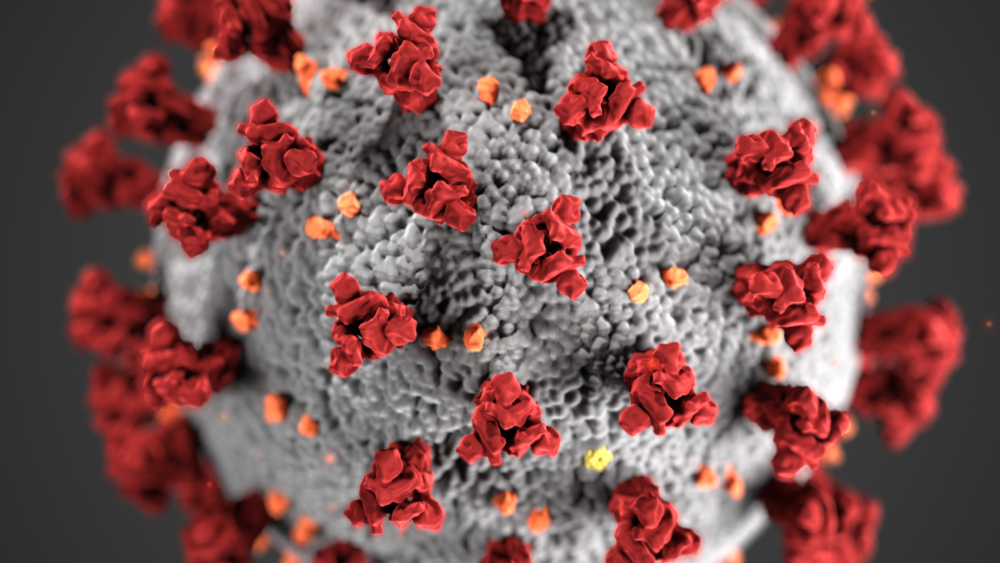

As the United States grapples with the escalating outbreak of COVID-19, the highly contagious and devastating coronavirus, education leaders across the country are facing difficult, enormously impactful choices.

Should they close schools?

For how long?

How can instruction continue outside the school environment?

Another important question that needs to be asked is:

How will school closures impact students with disabilities?

Key Takeaways for District and School Leaders

With the World Health Organization officially declaring that COVID-19 is a pandemic, a new sense of urgency has been introduced and we anticipate more schools will be closed. With this in mind, schools must think through the following critical considerations as they develop plans to educate students with disabilities.

- IDEA mandates that all eligible students have a right to a free and appropriate public education (i.e., FAPE as articulated in an IEP) even in times of crisis

- Schools/districts should convene IEP teams before changing student’s placements (i.e., shift to an independent-study, virtual, or online setting).

- Schools/districts that close and/or move to remote instruction may need to: a) provide appropriate technology and access to all students, keeping the principles of Universal Design for Learning in mind; b) provide wifi access/pay for it for Title I eligible families; c) ensure students have required assistive technology needs met/provided by the school; and d) provide [certain] services at home where appropriate.

- Accommodations, modifications, or other supports guaranteed under Section 504 must also be provided.

- Through this entire process, it is crucial that schools work closely with families to think and plan about how best to meet the needs of their children in what may be a chaotic and constantly-changing environment. These challenges can best be met together.

The Evolving Crisis

Education Week is tracking school closures related to the virus.[1] They report that, as of March 12, 2020, 2097 schools have been closed or are scheduled to close, affecting 1,305,611 students. There are 132,853 public and private schools in the U.S. and almost 50.8 million students, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. If the virus continues to spread, more and more district and charter schools are likely to close, creating educational challenges that may be unprecedented in scale and severity.

Although COVID-19 generally does not appear to be as dangerous to children as it is to older adults or individuals with higher risk factors, some may contract the virus and there is a risk that some could carry the disease back home with them. Adults in the school building may put themselves at risk of contracting or transmitting the disease by interacting with each other and with students. Closing schools may be viewed as a necessary step in slowing the spread of the virus.

But a decision to close schools comes with its own set of risks. Students suffer from the interruption of instruction, lost access to peers and trusted adults, and even food insecurity with the loss of school meals. Many working parents/guardians are unable to stay home with their children without risking the loss of employment, putting them in an impossible position. And teachers and administrators face the uncertainties of work instability, student learning gaps, and missed state test administration.

Districts and charter schools are exploring various approaches to closing or taking their instructional programs online. One common denominator is a lack of preparation—very few districts or schools appear to have a plan or resources in place to allow for a smooth transition to remote education. They are scrambling and doing their best to quickly pull together something that works. Such solutions have to address the needs of all students, including those with disabilities, because civil rights such as those guaranteed under IDEA exist even in a crisis.

Requirements for Serving Students with Disabilities

Students with disabilities have rights under various federal and state laws, most notably the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504), and the Americans with Disabilities Act (the ADA). These laws collectively provide such students with the right to special education and related services that are appropriate for their needs as well as the reasonable accommodations and modifications they need to access those offerings. Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) and student plans under Section 504 (504 Plans) identify each student’s needs and serve as a set of requirements, obligating state and local education entities to implement those programs, services, and supports. These are essential civil rights protections for vulnerable children. Federal and state legislatures and courts have uniformly found such rights under IDEA to be mandatory and non-negotiable, even when difficult or expensive to provide. Section 504 and the ADA are considered to have very high thresholds for any exceptions.

But what happens when a crisis occurs and schools cannot open or operate in any normal way? Natural disasters, localized health emergencies, and violent incidents periodically cause schools or even districts to close, and this can disrupt education for many students for a limited period of time. There are precedents and best practices for dealing with such partial disruptions.

COVID-19 may be unique in presenting a situation in which students learning together in any school building anywhere in the country could be considered a serious health hazard, with the hazard potentially lasting for weeks, months, or even longer. There have been other relatively recent outbreaks of infectious diseases, such as the H1N1 influenza outbreak in 2009, but this was much more limited in scope and geography. With the exception of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, no emergency for generations has had the capacity to simply shutter all of the schools in a particular city or region. COVID-19 has the potential to do just that. As educators scramble to find ways to deal with this sudden crisis and to serve families and students as best they can despite the turmoil, the education of students with disabilities must not be forgotten.

Again, such services under IDEA are not optional – there is no hardship exemption that state or local education agencies can fall back on.[1] Having said that, schools and districts will need to be intentional in their planning to fulfill obligations under IDEA.

The U.S. Department of Education released new guidance on March 12, 2020 (the March 12 guidance) specifically tailored to the current health crisis. The new guidance specifically addresses school closures and moving to other modes of education for students with disabilities:

Question A-1: Is an LEA required to continue to provide a free appropriate public education (FAPE) to students with disabilities during a school closure caused by a COVID-19 outbreak?

Answer: The IDEA, Section 504, and Title II of the ADA do not specifically address a situation in which elementary and secondary schools are closed for an extended period of time (generally more than 10 consecutive days) because of exceptional circumstances, such as an outbreak of a particular disease.

If an LEA closes its schools to slow or stop the spread of COVID-19, and does not provide any educational services to the general student population, then an LEA would not be required to provide services to students with disabilities during that same period of time. Once school resumes, the LEA must make every effort to provide special education and related services to the child in accordance with the child’s individualized education program (IEP) or, for students entitled to FAPE under Section 504, consistent with a plan developed to meet the requirements of Section 504. The Department understands there may be exceptional circumstances that could affect how a particular service is provided. In addition, an IEP Team and, as appropriate to an individual student with a disability, the personnel responsible for ensuring FAPE to a student for the purposes of Section 504, would be required to make an individualized determination as to whether compensatory services are needed under applicable standards and requirements.

If an LEA continues to provide educational opportunities to the general student population during a school closure, the school must ensure that students with disabilities also have equal access to the same opportunities, including the provision of FAPE. (34 CFR §§ 104.4, 104.33 (Section 504) and 28 CFR § 35.130 (Title II of the ADA)). SEAs, LEAs, and schools must ensure that, to the greatest extent possible, each student with a disability can be provided the special education and related services identified in the student’s IEP developed under IDEA, or a plan developed under Section 504. (34mCFR §§ 300.101 and 300.201 (IDEA), and 34 CFR § 104.33 (Section 504)).

This portion of the March 12 guidance essentially says that:

1) The relevant laws do not directly address how special education must be handled in a situation where schools are closed for an extended period of time, such as for a virus like COVID-19;

2) If an LEA is not able to provide any educational services to students, then it is not required to provide special education services but may be required to retroactively offer compensatory services once school resumes; and

3) If an LEA does continue to provide educational opportunities to the general student population during a crisis, it “must ensure that students with disabilities also have equal access to the same opportunities, including the provision of FAPE.”

The guidance also addresses circumstances where special education schools close, where students who become infected are out of school for extended periods of time and where schools consider including contingency plans in their IEPs. If you have questions about those issues, the complete guidance document is here.

On March 16, the Office for Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Education issued its own new guidance (the OCR Guidance): Fact Sheet: Addressing the Risk of COVID-19 in Schools While Protecting the Civil Rights of Students. The OCR Guidance covers some of the same ground as the Department’s March 12 guidance, but also more directly addresses the question of how IEP team meetings should be conducted during periods where school buildings are closed and communities are exercising social distancing. It states:

IEP Teams are not required to meet in person while schools are closed. If an evaluation of a student with a disability requires a face-to-face assessment or observation, the evaluation would need to be delayed until school reopens. Evaluations and re-evaluations that do not require face-to-face assessments or observations may take place while schools are closed, so long as a student’s parent or legal guardian consents. These same principles apply to similar activities conducted by appropriate personnel for a student with a disability who has a plan developed under Section 504, or who is being evaluated under Section 504.

Applying the OCR’s guidance, if the IEP team is unable to meet in person, they should meet by teleconference or other remote methods to make determinations about how a student’s needs can be met under whatever conditions now exist due to school closure and any quarantine that might be imposed on the student due to localized health considerations. The same is true for personnel implementing Section 504 Plans. If an evaluation requires a face-to-face assessment or observation, it should be delayed until the school reopens.

Strategies to Educate Students with Disabilities in the Event of School Closures

In the absence of a clear path for serving students in this crisis, the best approach may be to consider every available option. Consider the following to be the beginning of an exercise in brainstorming, to be enhanced and broadened through collaboration. Through this process, we encourage schools to communicate closely with families of students with disabilities to plan how they can best meet the needs of their children.

- Virtual/Online Education: Many states offer district and/or charter schools that provide instruction via the internet. Models can include fully virtual instruction or blended learning, which incorporates elements of traditional classroom and online learning. In the face of a shut down due to COVID-19, a switch to online education may be an attractive option. Making such a transition on short notice may be quite difficult— instructional practice, hardware, software, staff capacity, and the time (and possibly money) to develop them may be in short supply. Schools may have to provide computers, internet access, and other technological elements at no cost to students who lack such resources. Students with IEPs are also entitled to be educated together with their non-disabled peers in the least restrictive environment appropriate for their needs. Online options may be difficult for some students with disabilities to access. This can be particularly true for services such as physical and occupational therapy and social/emotional support, which may require in-person support. Fully online learning models usually require the participation of an adult on-site that can serve as a facilitator. For students with disabilities, it may be that the parent or other family member who may serve in that role lacks the specialized training needed to provide certain supports. Such challenges are not new—the virtual schooling environment has struggled from its inception to meet the full range of specialized student needs. There are a number of resources that address such challenges (although none that specifically speak to an outbreak like COVID-19). Most helpful is the website for the Center On Online Learning and Students with Disabilities (COLSD). COLSD was a cooperative effort of the University of Kansas, the Center for Applied Special Technologies, and the National Association of State Directors of Special Education. It collects and makes available numerous reports that address such relevant areas as promising approaches for increasing accessibility to online programs and supporting families in their role.

- Independent Study: Another approach to remote learning that some districts and schools may take is to utilize a program of independent study that does not rely on online offerings. Instead, students could work from packets of hard copy resources and related materials. Whatever the format of instruction, students with disabilities must be provided with the supports and accommodations called for in their IEPs and 504 Plans.

- Blended Learning: As noted above, “blended learning” is a term commonly used to refer to programs that have both a virtual element and an element based in a “brick and mortar” school building. Given the baseline challenges that COVID-19 presents to students being educated at the same location, conventional models for blended learning may not be viable. But it is also possible that a school’s program could draw on written materials and workbooks that are sent to students to complete at home. Such materials could also be paired with online elements. Students with disabilities would need to have access to whatever supports they need in order to make use of such materials. That may present similar challenges to those presented by online learning.

- IEP and Section 504 Teams: As districts and schools prepare for possible closure, it would be prudent for IEP and Section 504 teams to proactively meet to determine student needs and develop plans for providing services during any interruption. This could include a designation that the home is the appropriate placement for the duration of the crisis and a clear plan for what services can be provided online during the closure and which ones may need to be addressed through compensatory services once school is resumed. The critical piece of this is putting together a needs assessment that addresses the educational needs of the students with disabilities who are students at the school.

- Compensatory Education: The IDEA allows, in certain instances, for students with IEPs to receive services retroactively. This can happen when circumstances will not allow for service provision in the ordinary course of instruction—perhaps because of a student’s illness or his or her unavailability to receive services, or because a school failed to provide appropriate services in a timely way. Special education authorities may determine that a certain number of hours of particular services must be provided to the student at a later date to make up for those that were called for previously. As noted in the federal guidance, it may be that in some circumstances this approach could be used in connection with COVID-19 school closures. For example, a student who requires in-person physical therapy as a related service several times per week might be awarded a fixed number of hours of such therapy that would commence once a closure or quarantine related to the virus was lifted. Determining where to draw the line between services that a district or charter school must find a way to provide and those that could be deferred until later may be quite challenging and should be decided in the context of an IEP team meeting.

If the COVID-19 virus continues to spread, more schools will likely close and the need for creative approaches to meeting the needs of students in those locations will grow. Ideally, schools, networks, and districts will share their ideas and experiences with each other and leverage the opportunity for innovation to provide a collective set of options that can be used by all. It is essential that a school or district’s overall plan for how to respond to the health emergency includes a proactive, thoughtful approach to serving students with disabilities that is woven into the plan from the outset and does not treat the most vulnerable students as an afterthought.

[1] Education Week provides a helpful interactive map depicting closures and reopenings by location.

[…] A national center focusing on students with disabilities also has prepared information that families and educators may find useful. That’s available here: […]

[…] On Thursday, March 12, 2020, The Center for Learner Equity published guidance on school closures and students with disabilities. To learn more about supporting your SPED students during closures, click here. […]

[…] COVID-19 and Students with Disabilities […]

[…] The Center for Learner Equity: COVID and Students with Disabilities […]

[…] The U.S. Department of Education released new guidance on March 12, 2020 specifically tailored to the current health crisis. The new guidance specifically addresses school closures and moving to other modes of education for students with disabilities. More here. […]

[…] learning environments for all during this evolving national transition. It has also curated guidance and links to official regulations regarding educational services for students with disabilities, when schools […]